Beyond the Frame: How NeRFs, Splats, and Genie 3 are moving storytelling into new dimensions.

As most of the AI world focuses on the release of Chat GPT-5, I’ve been far more excited by the release of Genie 3 and how similar technologies might change the future of storytelling.

Why am I so excited?

Because it’s starting to feel like we might realize my dream of having something akin to a holodeck in my lifetime. (For those of you who aren’t Star Trek fans, please bear with me, this does have contemporary applications.)

A beginner’s guide to the holodeck

For the non-trekkies, the holodeck was a giant room that through the use of “holotechnology” could turn into a representation of any place, real or imaginary.

- Captain Jean-Luc Picard would use it as entertainment to immerse himself in the hard-boiled detective series of Dixon Hill.

- Commander Worf performed combat simulations.

- And Data and Dr. Beverly Crusher used it to learn ballroom dancing and the cultural norms of an upcoming wedding ceremony.

These use cases mirror why we watch documentaries: to gain knowledge, understand something foreign to us, and be entertained while learning.

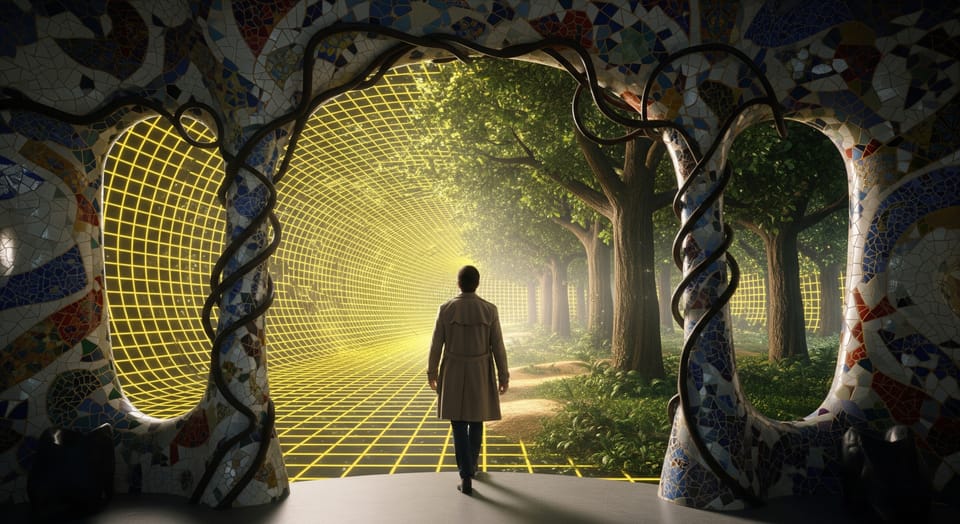

The promise of these technologies is that viewers become active participants in stories, not just passive observers.

Attempts to realize this form of storytelling are nothing new. Virtual reality has taken many forms over the past few decades.

The first commercial VR headset was featured in the movie Hackers 30 years ago, but despite attempts by Zuckerberg to make the Metaverse a dominant technology, or Apple’s efforts to convince everyone to wear immersive headsets with the Vision Pro, we are still far from mass adoption.

Two problems with immersive reality experiences

So why haven't we seen mass adoption of such promising technology? I think it comes down to two simple reasons:

- The best experiences require wearing a lot of gear.

- The data requirements are massive.

On the first point, many VR experiences require at least a headset and headphones. Some require gloves or wands to interact, and even more advanced systems involve haptic gloves or bodysuits. It’s just a lot of gear to take on and off. And of course, all that gear is a huge financial barrier to entry.

When I lived in Istanbul, my wife and I would regularly host “wine and VR” nights, inviting friends to try the latest Playstation VR mini games while the rest of us sipped wine and laughed at the person flailing around at virtual objects with glowing wands in their hands.

The people watching tended to have more fun. Not because of the wine (although I’m sure that helped), but because they felt more unburdened in social interaction than the person in the VR world.

Some artists have leaned into this sensation. One of the best VR films I ever saw was “After Solitary” by Nonny de la Peña and her studio Emblematic Group at SXSW. In the film you are listening to a convict tell his story in his small cell and you can feel every bit of the claustrophobia. It’s a brilliant design approach, in which the weakness of the medium is used to enhance the sensation of close quarters in solitary confinement.

But even in well executed films like that one, there is a limit to how long people want to wear all this gear. At the wine and VR nights, people rarely lasted more than 10 minutes before they wanted to take off the large visor and headset, and put down the wands and data transfer cables attached to them.

Which brings me to my second point. This stuff just takes a ton of data, and usually means being attached to large data transfer cables to make 3D immersive experiences work.

We're not talking about twice or three times the data of regular video. Depending on the quality level, we're talking anywhere from 5 to potentially 100 times more data to achieve resolution that’s close to what we expect in the real world.

And that’s just static 3D environments. Want to move around like it’s a video game? Even more data. Most of us who have ever played a console game are used to the polygonal models loading as we enter into a new area.

But recently, impressive new approaches have been gaining traction that have me excited about the possibilities in this space:

Strange names in the 3D space and what they mean

Capturing real world data

The process of recording physical spaces for digital reconstruction.

Photogrammetry

This is the basic act of taking a lot of photos of something from several angles so that a 3D version of it can be constructed later. This approach fuels the 3D models of things in Google Maps, or 3D virtual real estate tours that allow you to tour a home from a browser.

LiDar and other fun ways to use lasers

With LiDar (or other laser approaches like structured light scanning used in facial recognition, laser triangulation and Time-of-flight cameras) a device sends out lasers and uses light calculations to create a 3D map of points.

Synthesizing experiences

While several apps can transform photogrammetry into viewable experiences (think 360-degree cameras with photo-sphere renders), the truly exciting breakthroughs have emerged in the past few years through AI acceleration.

NeRFs (Neural Radiance Fields)

These use machine learning to transform basic photogrammetry into dynamic 3D scenes, calculating position, color, and transparency of every point based on your viewing angle.

Gaussian Splatting

This is an even more recent approach that is similar to NeRFs in how it uses AI to construct the 3D environment, but it does so in a way that is faster and more efficient. Simply put: it creates a point cloud where every dot has color, transparency, and location data, then "splats" these points onto your screen in the correct position based on your viewpoint.

The NY Times R&D lab recently experimented with Gaussian Splatting. It gives a good sense of the potential for this in journalism and other documentary use cases.

Creating something new and imagined

Compared to NeRFs and Gaussian Splatting, Genie 3 is closer to world building using CAD and other 3D modeling tools where objects and worlds are built from whole cloth. What is impressive is how quickly and accurately it can render worlds, and the level of object permanence as you move about in this world.

Instead of pre-rendering entire worlds before exploration, Genie 3 generates them frame by frame based on user movement.

It’s not hard to imagine what might be possible with this approach in the not so distant future. 3D practitioners are playing around with how to pair Genie 3 with Gaussian Splatting as we speak.

The fuel of holodeck dreams

Why does this make me dream of holodecks?

Imagine capturing a location with photogrammetry and LiDAR, but instead of rendering a frozen moment, the wind begins to blow through trees, water flows naturally, and clouds drift across the sky. New elements are being rendered that weren’t captured in real-time, but it brings you closer to a complete experience of what it was like to be in that space.

There are obvious concerns to consider about what gets created in these environments, and by whom. But it’s important to point out that all documentation is an abstraction of reality.

From the earliest days of celluloid film to modern digital sensors, cameras have always captured light information from a 3D world so that it can be visibly portrayed in a 2D medium. It is inherently incomplete, which is why the best cinematographers know how to “cover” a scene by capturing close up shots and a variety of angles so that a viewer feels a sense of place in the scene.

These tools may bring us to a moment where that sense of place is created not by lens choices and camera angles, but by other forms of creative direction paired with user behavior.

The traditional cinematic frame is likely to be with us for some time, and AI is rapidly evolving what is possible within that frame. But I wouldn’t be surprised if in the coming years we finally start to see an expansion beyond that frame.

To accomplish this requires two things to evolve in parallel: the display and the content engine.

The content engine is already taking shape with tools that can synthesize reality and dynamically create worlds, like NeRFs, Gaussian Splatting, and Genie 3.

The display is evolving down two exciting paths. One path leads to our environment itself becoming the screen, like a personal version of the Las Vegas Sphere. The other leads to radically lightweight wearables—glasses that are as unobtrusive and personal as the smartphone is today.

I haven't had a chance to use Genie 3 yet, but just watching the demos, I can already imagine the world where those paths converge. It’s a world where the immersive experience of a holodeck is no longer science fiction, but the emergence of a new form of visual storytelling.